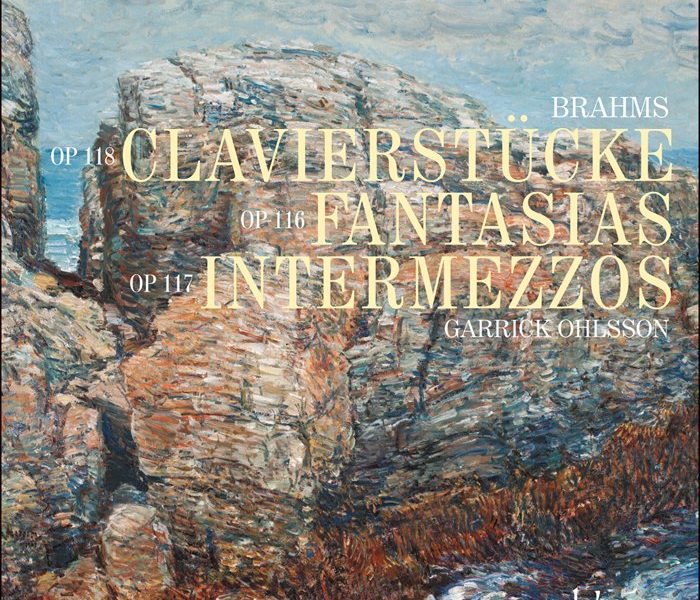

Brahms: Late Piano Works

This album will be released on December 28, 2018 for digital download (iTunes) and January 4, 2019 for physical copies (Amazon), where it is already available for pre-order.

From Hyperion:

‘By the way, has it struck you that I have clearly said my farewell as a composer?’, Brahms asked his publisher, Fritz Simrock, in September 1894. His question was prompted by the fact that the last of the forty-nine German folk songs he had collected and arranged in the spring of that year was the same traditional melody he had used more than four decades earlier in the slow movement of his piano sonata, Op 1. The melody, Brahms told Simrock, ‘represents the snake that bites its tail—and thus states with pretty symbolism that the tale is finished.’

For some years, in fact, Brahms had regarded his life’s work as more or less over. Following his G major string quintet, Op 111, of 1890, he confided to his friend Eusebius Mandyczewski (the future editor of his collected works) that recent attempts at other large-scale projects had come to nothing, and that he was now perhaps too old to continue. The following year, in what had become his favourite summer resort of Bad Ischl in the Salzkammergut region of Austria, Brahms wrote his will. But reports of his artistic demise turned out to be much exaggerated: it was also in 1891 that he met the clarinettist Richard Mühlfeld—an encounter that inspired him to compose his clarinet trio and quintet, Opp 114 & 115. Two sonatas for Mühlfeld (Op 120) were still to come. And in 1892, again in Ischl, Brahms began work on the twenty piano pieces that make up the four collections published as his Opp 116-119.

Much of the music of Brahms’s final years seems to be permeated with forebodings of death. His last work, written in the wake of Clara Schumann’s funeral in 1896, was a set of eleven chorale preludes for organ, ending with ‘O Welt, ich muss dich lassen’ (‘O world, I must leave you’). That same year he had composed his Vier ernste Gesänge (‘Four serious songs’), one of which sets the words ‘O Tod, wie bitter bist du’ (‘O death, how bitter you are’), to a descending chain of thirds—a melodic interval which came to stand in Brahms’s late music almost as a symbol of death. The same interval is prominent in several of the piano pieces of this decade.

Listening to Brahms’s piano pieces of 1892, we may imagine him deriving solace from them as he composed, or perhaps initially improvised, them. This was a time when he saw many of those closest to him die: his sister Elise and his long-standing friend Elisabet von Herzogenberg in 1892; the singer Hermine Spies (at the age of only thirty-six) the following year; and in 1894 the Bach biographer Philipp Spitta, the pianist and conductor Hans von Bülow and the surgeon Theodor Billroth.

Fantasias, Op 116, is a curious title for a collection of pieces consisting of three capriccios and four intermezzos. Brahms had used the same labels of ‘capriccio’ and ‘intermezzo’—again to indicate a division between agitated and more serene pieces—for the individual numbers of a similar collection he had composed some fourteen years before; these earlier pieces had appeared under a more neutral banner as eight Clavierstücke, Op 76.

Brahms sent the Op 116 pieces to Fritz Simrock with the instruction that they should be issued in two volumes of three and four pieces respectively, though in view of the exceptionally strong unity underlying the set as a whole the composer’s desire to divide it in this way was surprising. The last number, like the first, is a stormy D minor capriccio; while at the centre of the collection stand three intermezzos in E major and minor which together may be construed as a form of slow movement. Moreover, the interval of the falling third is everywhere in evidence—not least, right at the beginning of the impetuous opening number. The sarabande-like theme of the melancholy A minor intermezzo which follows, with its fleeting, shadowy middle section, is again permeated by the same melodic shape.

The third piece, a passionate G minor capriccio with a grandiose trio section, functions as the scherzo of the set. Its initial phrase, which returns in an imposing augmented form to round off each of the two outer sections, is once more characterized by descending thirds; and the very same phrase returns in the decorated reprise of the following E major intermezzo’s main theme. The latter piece, which Brahms originally called a nocturne, is one of his most perfect miniatures, and an object lesson in how to fashion a deeply satisfying composition out of the greatest possible economy of means.

‘Andante con grazia ed intimissimo sentimento’ is the evocative tempo marking of the E minor intermezzo No 5. Its sighing two-note phrases, invoking strikingly dissonant harmony, at first give no hint of the music’s actual metre, which is revealed only in the more consolatory middle section. The E major penultimate piece, on the other hand, begins without any preamble in the style of a nostalgic, bittersweet minuet. Its theme is two-stranded, with a broad and expressive chromatic inner line surmounted by a series of stepwise descending phrases.

The concluding capriccio is in Brahms’s most agitated style, with the music’s restlessness reaching a peak in the middle section. The final bars recall the rhythm and harmony of the opening number, thereby bringing the collection full-circle.

Brahms once referred to the three Intermezzos, Op 117, as ‘the cradle songs of my grief’. Only the first of them is an actual lullaby, though the predominant dynamic marking throughout the set is either piano or pianissimo, and all three pieces are quite similar in tempo and mood. At the head of the first piece Brahms quotes two lines from Johann Gottfried Herder’s translation of an old Scottish poem: ‘Sleep gently, my child, sleep gently and well. It grieves me much to see thee weep.’ In the minor-mode middle section, with its softly drooping intervals, we can, indeed, almost picture the tears flowing.

The second piece is more agitated, though this time it turns for its middle section from minor to major, in a consolatory transformation of the opening material. The middle section of the deeply melancholy final number, in a slightly quicker tempo, is restlessly syncopated throughout; while the reprise of the opening theme is prefaced with heavy-laden phrases whose falling intervals once again evoke Brahms’s symbol of death foretold.

With the six Clavierstücke, Op 118, the title ‘capriccio’ disappears altogether, while two new headings make their appearance: ‘ballade’ and ‘romance’. Both the ballade and the romance of Op 118 (Nos 3 and 5) have a middle section in a distant key, casting a glow of warmth over the music. In the ballade the smooth pianissimo melody of the B major middle section in caressing thirds and sixths, played with the soft pedal, offers a strong contrast to the full-blooded staccato chords of the G minor outer sections. Rather than bring the piece to an emphatic close, Brahms reintroduces the opening strain of the middle section’s melody during the final bars, this time in the home key. The middle section of the romance, on the other hand, maintains the intimate atmosphere of the remainder of the piece, while allowing the music to accelerate into a graceful allegretto. This allegretto’s thematic outline clearly derives from the inner voice of the andante’s main melody.

The opening intermezzo differs from the remaining pieces of the collection in that it appears to unfold in a single spontaneous sweep. Moreover, the opening bars, with their F major undertones, do nothing to define the key of the piece, which is revealed only in the closing bars as the music comes to rest on the chord of A major.

The gentle second intermezzo is among the most famous of Brahms’s shorter pieces. The melody of its middle section, in a melancholy F sharp minor, is answered in the left hand by a hidden canon in longer note-values. Following the ballade, Brahms offers a shadowy intermezzo whose subdued agitation is countered by a middle section of extreme stasis, in which the pianist’s hands continually echo each other in curiously out-of-phase fashion.

The dark key of E flat minor is one that seems to have been associated in Brahms’s mind with a particularly bleak mood, and it is surely not by chance that the heading of both the slow third movement of the Op 40 horn trio and the last of the Op 118 piano pieces contains the word ‘mesto’ (‘sad’). The piano piece seems to carry with it a suggestion of orchestral sonorities: a clarinet, perhaps, for the unaccompanied opening melody, punctuated by sweeping diminished-seventh arpeggios evoking the sound of a harp, which cut through the music like a chill wind. The middle section is a solemn march whose impassioned culmination overlaps with the reprise of the opening melody. At the end, the melody rises to another short-lived but despairing climax, before a slow ascending E flat minor arpeggio draws a final curtain of gloom over the piece.

Also in E flat minor, but in a more heroic vein, is the Scherzo, Op 4—the earliest of his pieces which Brahms sanctioned for publication. He was just eighteen at the time he composed it, in the summer of 1851. The tense, hesitant way in which it begins may remind us of the second of Chopin’s four scherzos, in the closely related key of B flat minor, though Brahms’s splendidly energetic piece is already highly characteristic of his own individual style. Following its spasmodic opening, the scherzo itself presents a more conjunct second subject, introduced by the left hand in the manner of a pair of horns. In the scherzo’s concluding bars a rushing scale from the top of the keyboard to the bottom heralds a more forceful variant of the same subject.

Brahms provides two trios, the first of them deriving its energy from the manner in which the initial leap of its main motif continually overshoots the interval of an octave by a whole tone. The second trio, in a luminous B major, is more lyrical, with a yearning, syncopated initial idea giving way to a Chopinesque melody above a ‘rocking’ left-hand accompaniment. The trio’s latter half is punctuated by distant reminiscences of the scherzo’s opening motif out of which Brahms eventually fashions a seamless join to the full return of the scherzo itself.

Misha Donat © 2019

Critical acclaim:

Politiken – Top 20 albums of 2019

“The American pianist Garrick Ohlsson, a player with a big sound and equally generous sensitivity, has grouped three Brahms sets – Fantasias Op 116, Intermezzos Op 117 and Clavierstücke Op 118 – on Hyperion. This late outpouring, after Brahms had threatened creative silence, encompasses all the composer’s moods and characteristics. The quirky, faltering gait of Op 116 No 5 in E minor, the capacious desolation of all three Op 117 intermezzos and the major-key grief of Op 118 No 2 in A major, elusive music that separates those who can play Brahms and those who can’t, are handled with tireless perception and not a shred of bombast. It makes addictive listening.”

- Release Date:

- December 28, 2018

- Number of Discs:

- 1

- Label:

- Hyperion Records Limited

- Copyright:

- (C) 2018 Hyperion Records Limited

- Total Length:

- 71:32